“Nostalgia,” in The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, eds. Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann (Routledge, 2020), 156–59.

[In lieu of an abstract, here is the opening paragraph]

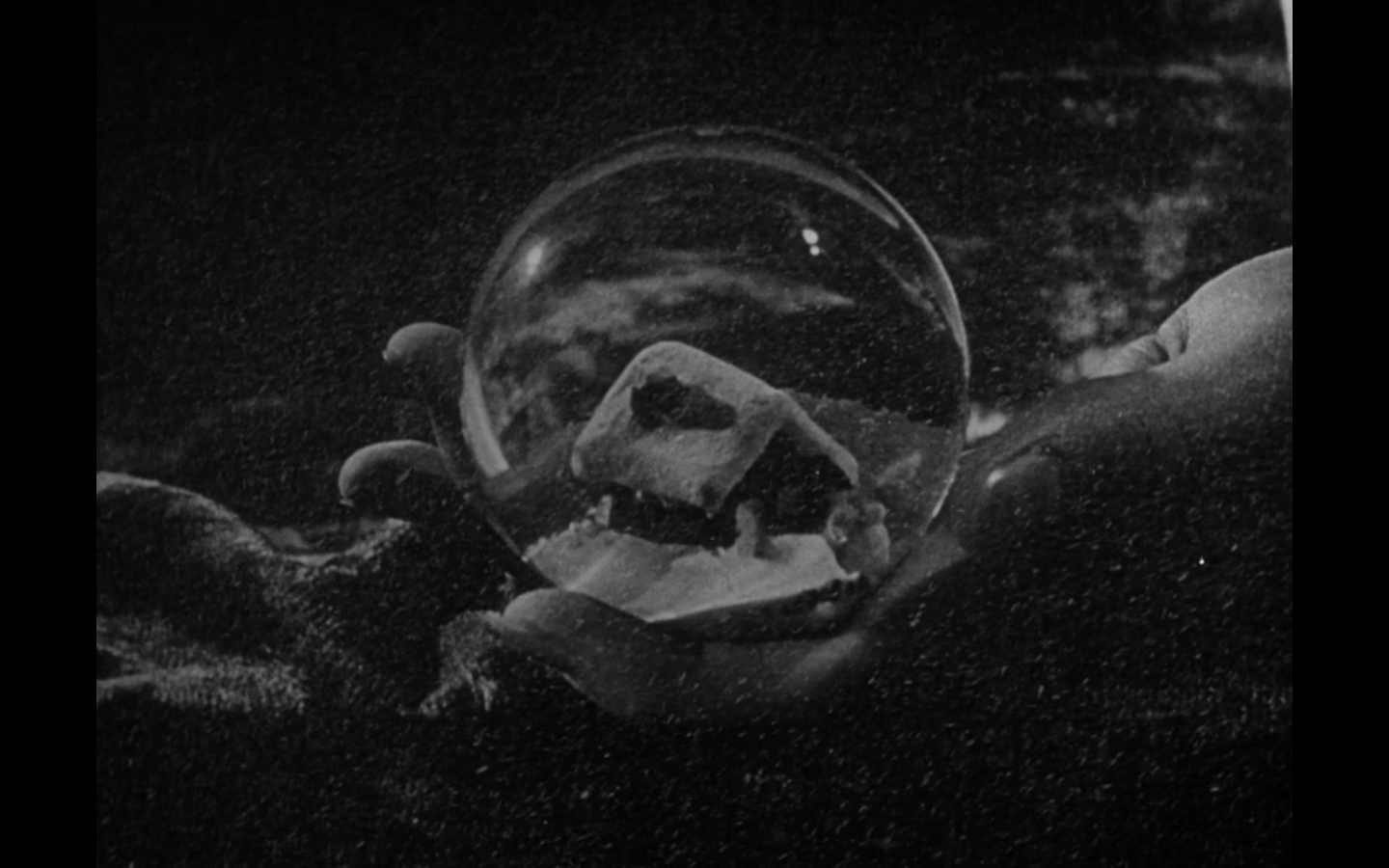

Nostalgia designates a domain of historical practice that is often said to be antithetical to historiography’s production of historical meaning.Whereas this latter mode is typically predicated upon the exercise of reason, narrative figuration, historical distance, and a focus on shared experience, nostalgia designates a mode that prioritizes affect, imagery, intimacy with and absorption in the past, and autobiographical experience. In other words, nostalgia belongs to, as philosopher Steven Galt Crowell puts it,“spectral history—not the story of the public unfolding of a self, but an experience of the past as impossibly one’s own, a return of the dead, evidence of the ego’s resistance to the all-unifying structure of time” (Crowell, 1999, p. 84; emphasis in original). It is on the basis of its particular weave of desire with emotion, memory and commemoration, body and embodiment, and the quest for authenticity that nostalgia is frequently linked with practices of reenactment, and often distrusted by historians, anthropologists, poststructuralists, and others who use negative valuations of the concept to shore up their own group identities.