“The Painting of Modern Light: Local Color Before Regionalism,” American Literature 86, no. 3 (2014): 551–581.

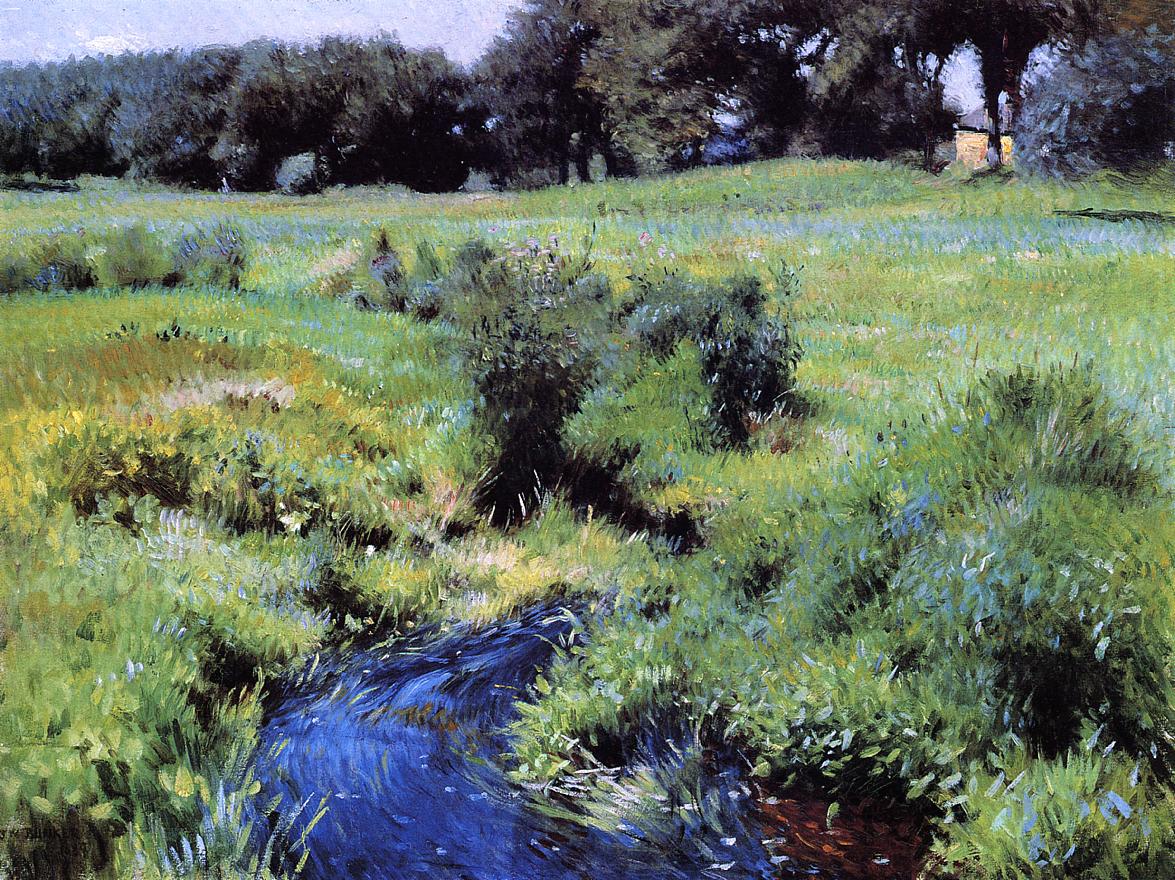

This article works to draw critical attention to the aesthetic history of local color, and, more broadly, to the underrecognized relation between local color and realism. In returning local color to its long aesthetic history within painting, Schroeder argues that its primary purpose within realism was not the delineation of regions, but rather the production of an affective and aesthetic engagement with the cosmopolitan project of self-cultivation. The local-color detail was generally not used as a representative detail of a place, but rather, by the late-nineteenth century, as an indexical trace of the invisible truths of an object, and particularly the invisible processes that made human populations distinctive. By bringing this attention to local color’s color, Schroeder aims to move critical debates away from considerations of place-based content of local-color stories and toward a recognition of how local color constituted an aesthetic that could be configured in radically antithetical ways by an archrealist like Mary Murfree and an impressionist like Hamlin Garland. Ultimately, local color helps us see realism not as an indiscriminate, antiliterary, transparent representation of the world, but rather as a highly discriminating, distinctive style that was consistently engaged with the twin principles of human self-cultivation and the neoclassical economy of representation. The example of Garland’s Crumbling Idols has proven so illuminating for this essay precisely because of how it reacts against this formation, as well as how it suggests an alternative, unconscious receptivity to the detail that foreshadows American modernism and regionalism.