“The Wreck of Reason: Nostalgia by Land and by Sea,” in The Cultural History of the Sea in The Eighteenth Century, eds. Margaret Cohen and Jonathan Lamb (Bloomsbury, 2021), 135–153

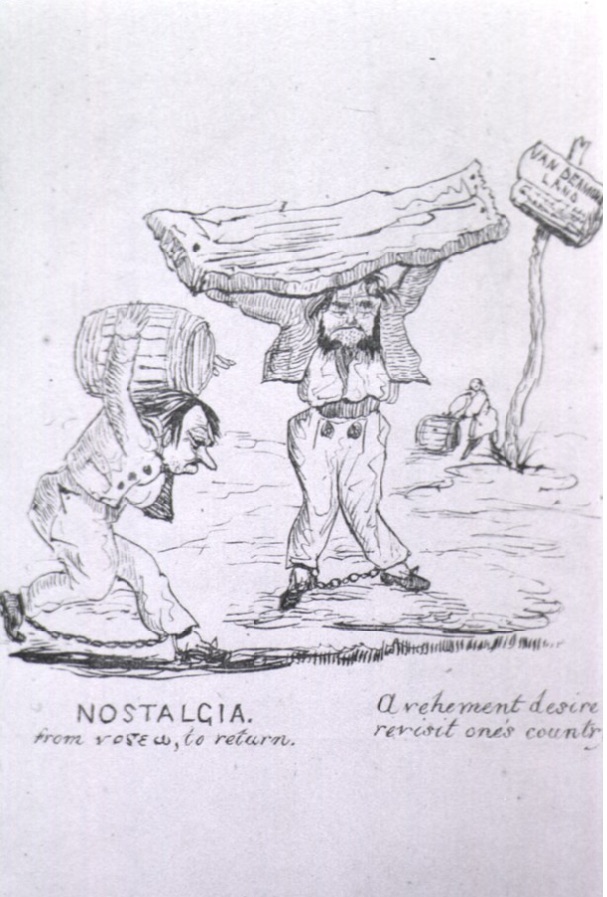

This essay concerns two major turning points in the history of medical nostalgia: the sea and the colony. In the eighteenth century, physicians conceptualized nostalgia as a disease of forced or coerced migration that ethnic Europeans, including Swiss mountaineers, Scottish Highlanders, and Laplanders, were particularly vulnerable to on account of their stronger “local attachments” to their homelands. At the turn of the nineteenth century, however, the sea became a stubborn fact that physicians had to reckon with when they carried the concept of nostalgia from Europe to the Americas in the late eighteenth century, initially for the purpose of mastering a motley assortment of masterless men and women, the mariners, renegades, and castaways who populated the early republic of the United States and dominated the archipelagic imagination of the Caribbean. In so doing, the sea supplied authors with a vocabulary for the degeneration of the body and an occasion for resistance against bondage. Poems like William Wordsworth’s “The Brothers” (1800) and Herman Melville’s “On a natural monument in a Field of Georgia” (1866) use this vocabulary to mount humanitarian critiques of war, economy, and medicine, which habitually ignored the role of labor conditions in inducing mental illnesses like nostalgia.